On Covid, corvids and coming home to Country: A lesson in fractal belonging

Published 8 July, 2022

“I live my life in widening circles, that reach across the world”, observes Rilke in Joanna Macy’s translation of his poem Widening Circles. Whereas I notice the direction of travel in my own life has taken a turn the other direction. My world has become smaller, quickly. I am not the great storm, or the song. Nor the falcon, though perhaps still a bird.

I have also noticed that life has a way of listening to what I espouse and gifting me the opportunity to take it a notch deeper. Two weeks ago I wrote about resting in the trough of the waves, so it should come as no surprise that – while on a winter getaway to sunny Queensland – I finally succumb to Covid. Fortunately, my husband and son were able to continue with the planned time away with friends in Far North Queensland; my own holiday destination was recalibrated to the front room of my mother’s house, on the sleepy Redcliffe Peninsular north of Brisbane.

A different Rilke poem comes to mind…

“Quiet friend who has come so far,

feel how your breathing makes more space around you.

Let this darkness be a bell tower

and you the bell.”

For the first few days all attention to breathing was purely clinical, but fortunately my symptoms eased, and I was able to revert to the poetic again. And as I resurfaced, I realised that although I am disappointing to miss the tropical warmth and time with friends, what I have here is a gift. Five full days of quiet and rest. With good food prepared for me and no caregiving responsibilities – this was in fact the utopia I’ve been waiting my entire motherhood for!

I discover it isn’t so quiet though. The local lads have penchant for noisy mufflers. Chatty retirees and their yappy dogs pass frequently on their way to the foreshore. Traffic hums day and night. But it’s the local murder of corvids that are most irritating.

Mum tells me stories about the crows. One hot summer they were destroying her lemon crop. Frustrated at first, she began watching and realised one was panting with thirst. She placed a large bowl of water in the garden, placed a helpful brick beside it, and soon all the crows in the neighbourhood were visiting for a refreshing drink and a splash (one clumsy crow frequently fell in). After that her lemons were safe. Sometime later a neighbour found a dead crow in his yard. He placed it under the she-oaks in the median strip. Crows came from all around to look at it. Apparently this is something they do to learn about threats. There was silence, then a great noise. After that they flew away and weren’t seen for many months.

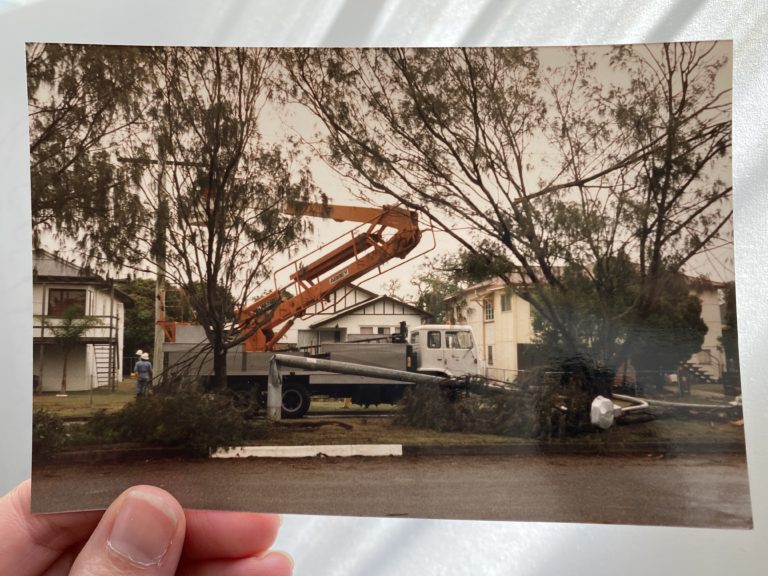

Looking out my window to those she-oaks I also see a streetlight. Christmas Eve 1989, I was six. A ‘tornadic supercell’ hit the region with winds of more than 100 knots (185 kph) on the Peninsula – bending the predecessor of that light pole to the ground.

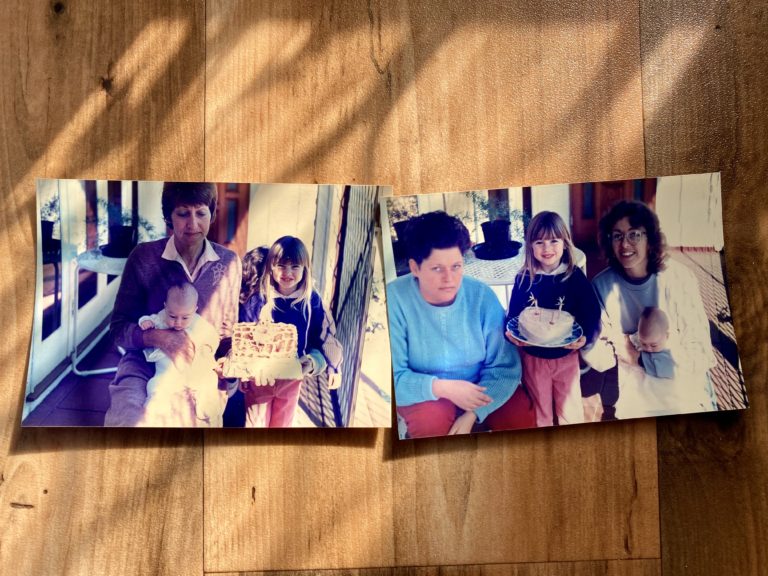

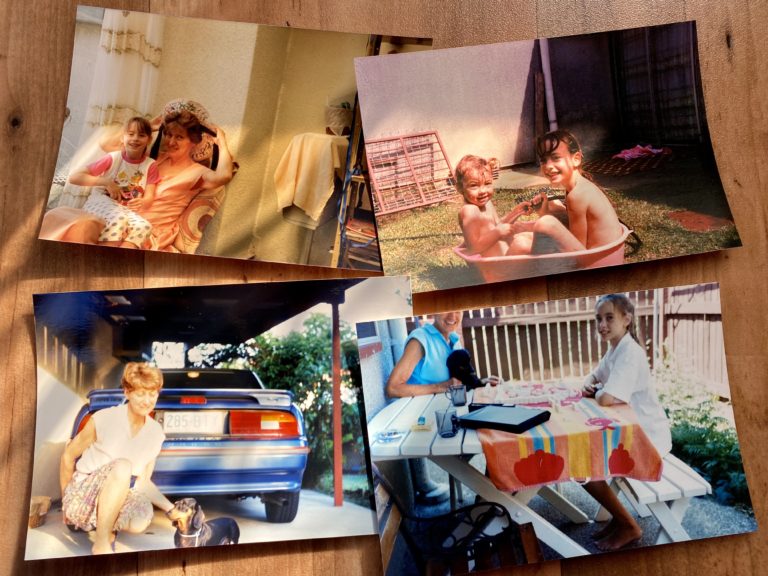

Years passed. My family moved from Western Australia to Vanuatu and then North Brisbane. Traditions of cherries and German gingerbread on Christmas Eve lived on, along with the smell of burning moxa and herbs from my grandmother’s Traditional Chinese Medicine practice (the room I’m staying in now). Her beloved dachshunds. Mahjong. My grandmother lived here until her death when I was in late high school. My aunt too. Sometime after my sister and I had left home, my parents moved here, and Mum stayed on when they divorced. While living in London my visits back to Australia were sporadic. Home has always been a difficult concept for me.

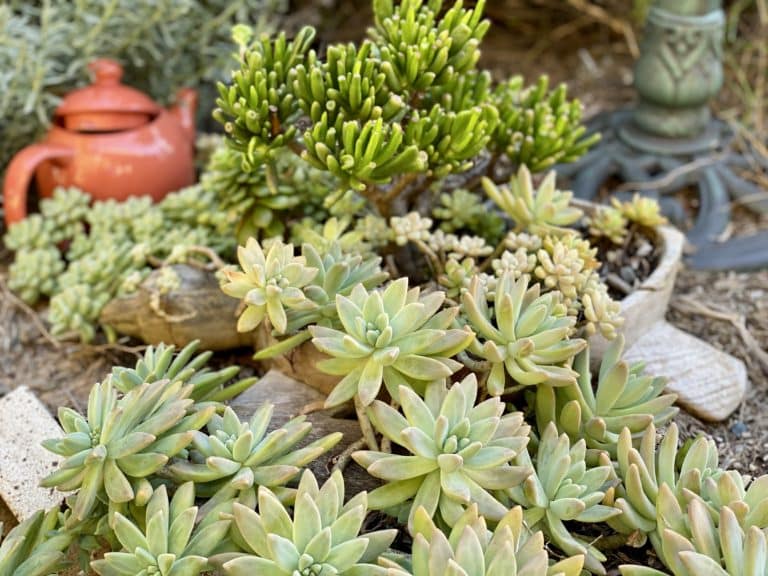

Sitting in the winter sunshine this afternoon, my eye is caught by my sister’s ceramics, bursting with succulents. So too is a turtle-shaped fruit bowl my Dad and I chose for Mum’s 40th while we were in Vanuatu. Mum has taken a turn for minimalism indoors, but this doesn’t apply to her gardening. Although this house has never been my home, I’m beginning to understand that it is still a place I am from.

This might be changing though. I have read in the news that within a decade rising sea levels will mean much of this area is uninsurable. I am reminded that the attractive picnic ground and recreational spaces on the foreshore are reclaimed land from the sea – a euphemism for those trucks dropping smelly landfill here during the 80’s.

The dawning realisation that I have geographical roots – and might be losing them soon – is disconcerting. My grandmother only moved to the Peninsula in the 70’s, and Europeans arrived here just shy of 200 years ago. Before that, this particular coastline was the home of the Gubbi Gubbi and the Ningy Ningy people, part of the Undambi people whose land stretched from Noosa Heads to the Brisbane River and inland to the Glasshouse Mountains.

It is NAIDOC week in Australia, where we celebrate and recognise the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – the oldest continuous living cultures on earth. This week of enforced isolation has made me acutely aware of my immediate geography, so I spend the afternoon time watching videos of teachers and Elders from this region.

I learn how the language is still present in our place names – Beerburrum (“the sound of the wings of a king parrot”), Kondalilla Falls (“rushing waters”) and Kippa-Ring (a nearby ceremonial site where boys’ initiation rituals were performed). I also hear heart-wrenching stories – not just the massacres during early European settlement – but also first-hand accounts such as this interview with Aunty Flo Watson OAM of the Stolen Generation.

Rile’s poem continues…

“As you ring,

what batters you becomes your strength.

Move back and forth into the change.

What is it like, such intensity of pain?

If the drink is bitter, turn yourself to wine.

In this uncontainable night,

be the mystery at the crossroads of your senses,

the meaning discovered there.

And if the world has ceased to hear you,

say to the silent earth: I flow.

To the rushing water, speak: I am.”

Like the way the air shimmers above hot ground, there’s a sense of something fractal emerging from this place. Echoing patterns of the bittersweet – love, loss, impermanence, beauty, belonging – reflected in the lives of all living things at all scales. Like the curves within a nautilus shell, perhaps this is what Rilke had in mind when he spoke about life moving in widening circles across the world?

Recognizing that the bittersweet is fractal has the power to transform our perception of the world we live in and our role to play. Between the edges of reality and the transcendent lies potential – a catalytic spark of creative vitality arising from the way we attend to our personal and collective cracks.

Aunty Flo’s words about reconciliation catch my attention, “But we just need people to know through our truth telling that those things did happen. And you can’t change history. But you can let people know that did happen and we are moving forward.” Acknowledgment and reconciliation are two actions that help us foster that spark, to weave the light and the dark of our lives and history into a life sustaining force that emerges from this place, from Country.

As I get ready to emerge back into the wider world in a few hours, I’m conscious of how much has changed for me from this encounter with Covid, corvids and Country. Acknowledging the ‘what is’ of my own personal connection with this place has opened me up to an unexpected sense of belonging.

Notes and acknowledgements

- General inspiration came from reading Susan Cain’s beautiful new book ‘Bittersweet‘ this week, alongside my ongoing interest and coursework in regenerative design principles drawing on people such as Daniel Christian Wahl

- Rilke’s two poems were Widening Circles and Let This Darkness Be a Bell Tower

- Aunty Flo Watson OAM’s three-part interview with the Moreton Bay Council can be found here. I found her capacity to hold the bittersweet deeply moving and inspiring.

- And in closing, my mum and I have managed to keep her testing negative this week!